.

.

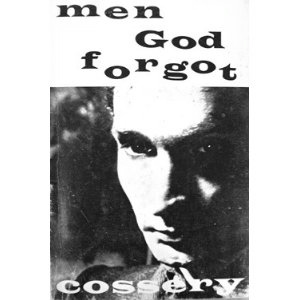

A Special Publication of the Library of America, this is a generous volume. It contains a three-page preface by the book’s editor Ron Padgett (a poet whose friendship with the author dates back to their high school days in Tulsa, Oklahoma); a ten-page Introduction by novelist Paul Auster; followed by over 500 pages of writings interspersed with the author’s own drawings and cartoons. Rounding out the book are pages of helpful editorial content: a Chronology; a Note on the Texts; and a Glossary of Names. The names belong to fellow artists, writers, dancers, musicians and associates mentioned by the shy-but-gregarious, serious-but-gossipy, frivolous-but-solemn, Joe Brainard.

The volume leads off with I REMEMBER, the autobiographical book Edmund White once labelled “a completely original book” and Paul Auster calls “a modest little gem.” There is an undeniable charm and relentless spell to it. Baby Boomer readers especially will be nodding their heads non-stop in recognition:

“I remember putting on sun tan oil and having the sun go away.”

“I remember catching lightning bugs and putting them in a jar with holes in the lid and then letting them out the next day”

“I remember Christmas cards coming from people my parents forgot to send Christmas cards to.”

“I remember red rubber coin purses that opened like a pair of lips, with a squeeze.”

“I remember wax paper.”

Over the years the simple template of I REMEMBER has influenced thousands of students in American creative writing classes, jump-starting imagination. Foreign writers too have followed its trail. One is Édouard Levé, whose Autoportrait is a pour of thousands of self-contained, self-referential declarative sentences — chips off the Brainard block.

And yet I REMEMBER fills only the first quarter (pages 3-134) of this Collected Writings volume. The bulk of the book falls into the category of Miscellany. To get a sense of the scope of these nearly 100 pieces, see the book’s Table of Contents on the Library of America site, here. Truth to tell, these pieces, which cover the hunt for love to the hunt for cigarettes and everything in between, include many misses among the hits. Take for example the illustrated piece on page 391 entitled “Matches.” It reads in its entirety: “If I strike say 60 matches a day (and I do) in a year’s time that would be — let me see — that would be — I hate math.” But the prevailing tone is a winning youthful energy, casual, humorous, miniaturistic. In his 1971 “Bolinas Journal” (reprinted at pages 285-333), he revealed his credo as simply “trying to be honest.”

Without doubt this book will appeal to Brainard “completists” — readers so taken by the delights of “I Remember” that from this intimately personal raconteur, from this easy sharer of confidences, they demand to hear more, more, and more.

The critic Michael Dirda recently observed that while THE COLLECTED WRITINGS “may not be a fully canonical Library of America title,” it is still “a superbly engaging bedside book.” I agree. After the opening section devoted to the minimalist yet somehow magisterial “I Remember,” this becomes a book to be dipped into at leisure.

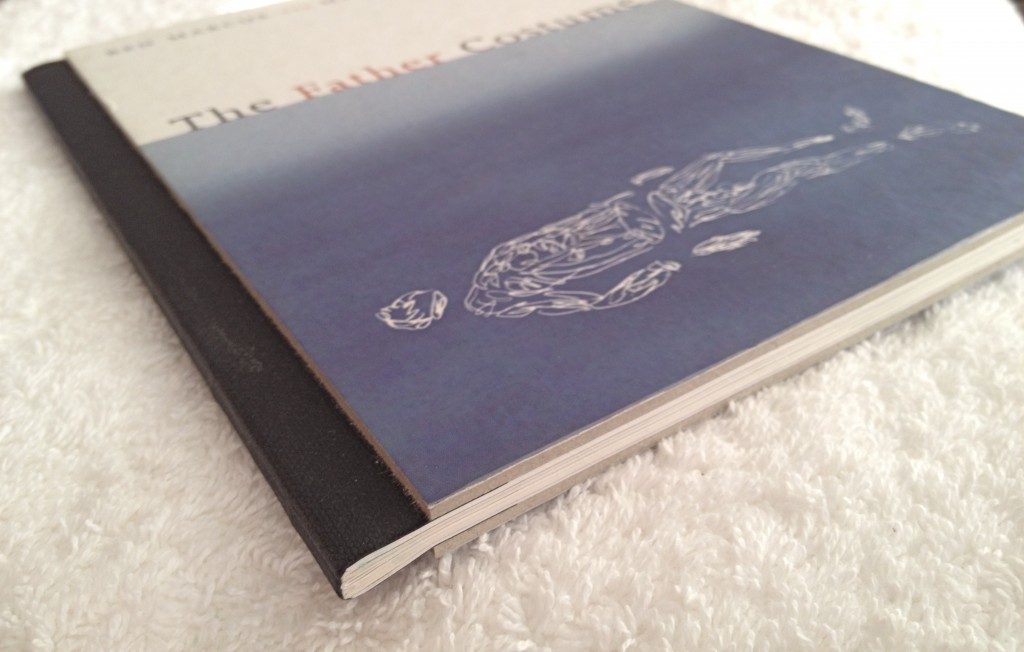

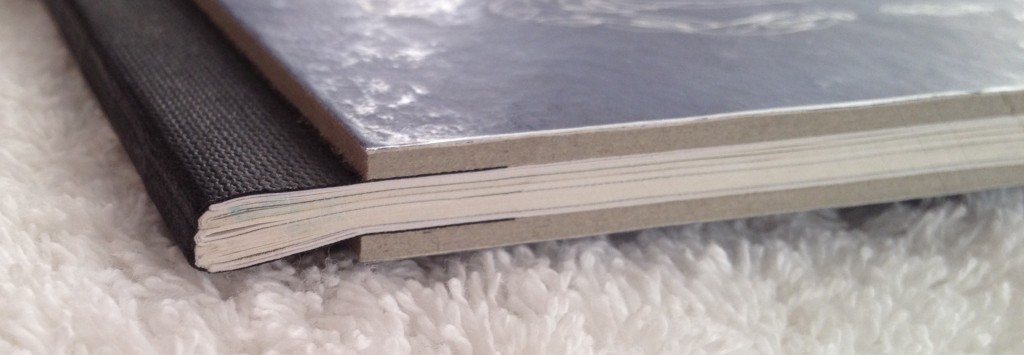

A note to readers who care about books as objects, especially the matter of their binding: Unlike volumes in the main Library of America series which are Smyth sewn (allowing you to open the book wide and bend back the covers without “breaking” or otherwise harming the binding), THE COLLECTED WRITINGS OF JOE BRAINARD is a “Special Publication” that features a different design and production. The trim size is larger (good), but notch binding is used here, a disappointment as it renders the book less elegant than regular LOA volumes.

I see I’ve used a lot of numbers in this review. A final one is 52. That is the age of this still-young author at the time of his death in 1994. The coldness of numbers masks the warm effect of THE COLLECTED WRITINGS OF JOE BRAINARD. In its pages you meet a big-hearted guy.

.

[A version of this review appears on Amazon, here.]

.

04-07-2012: This morning I came across an adoring review by Alberto Mobilio in the April/May 2012 online issue of Bookforum, here. Mobilio argues, convincingly, that “I Remember” is best read as an incantatory poem, one that epitomizes “that peculiarly American aspiration to self-mythologize in the face of an otherwise relentlessly quotidian world.”