.

.

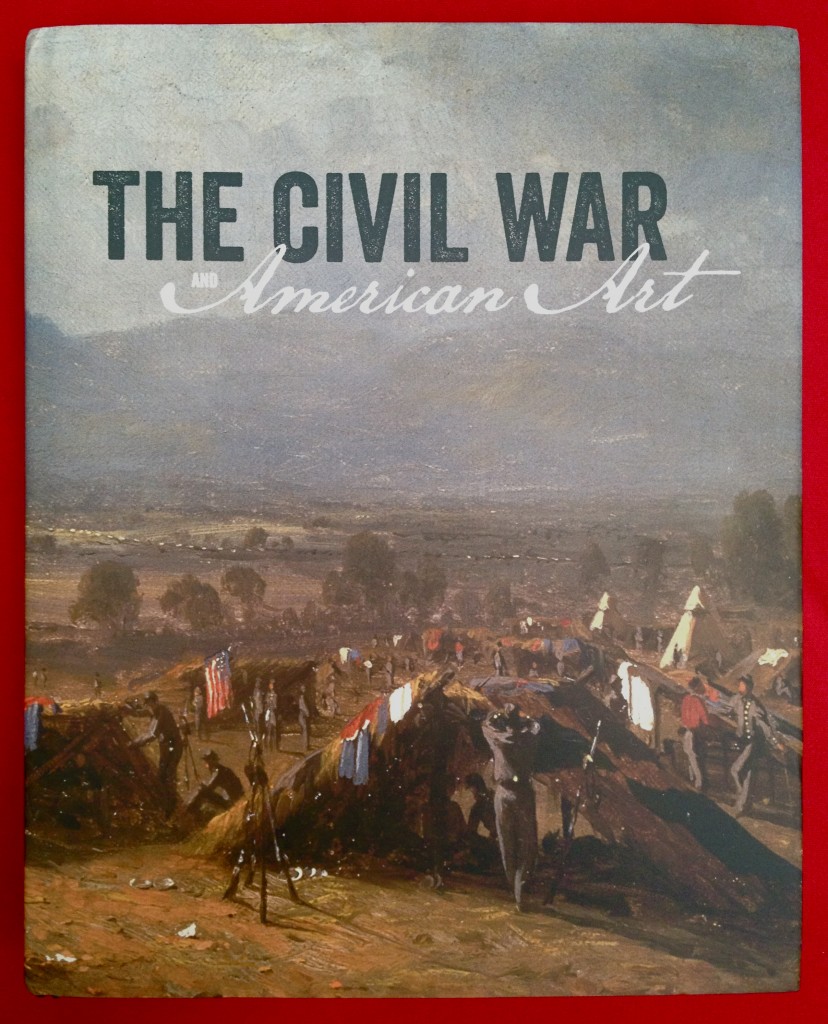

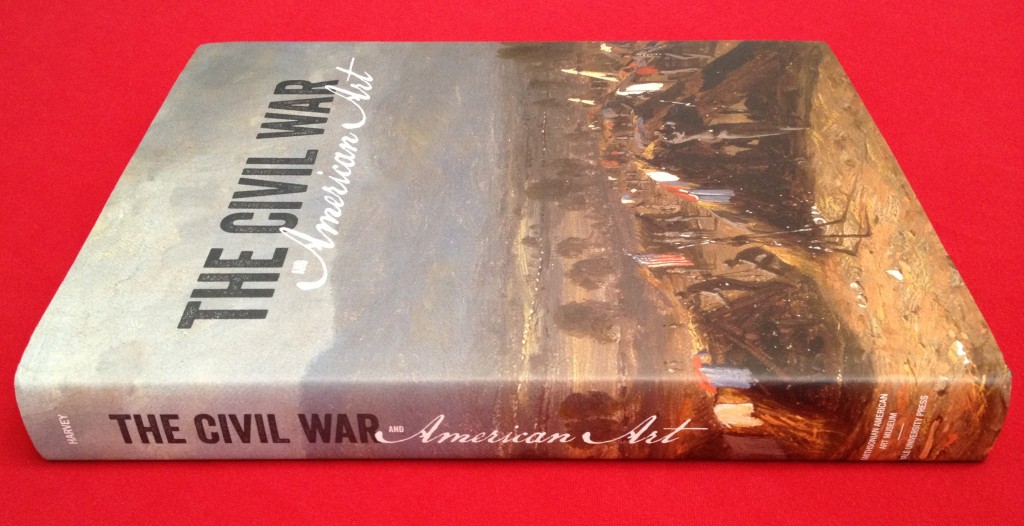

This book is published in connection with the museum exhibition of the same name, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, from November 16, 2012 through April 28, 2013. The show will travel to New York City where it will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of American Art from May 21, 2013 to September 2, 2013. Both the book and the museum exhibition are experiences of such quality that they will appeal to persons beyond the camps of Civil War buffs and lovers of American Art. For me the exhibition is a must-see. The book? It is a must-have.

What impresses is how successfully all elements of the book converge.

First and foremost is the text. Eleanor Jones Harvey’s thesis is a simple one: “The Civil War had a profound and lasting impact on American Art, as it did on American culture. Both genre painting and landscape painting were fundamentally altered by the war and its aftermath.” As well, she demonstrates how photography–the third of her areas of interest–was newly empowered as an art form.

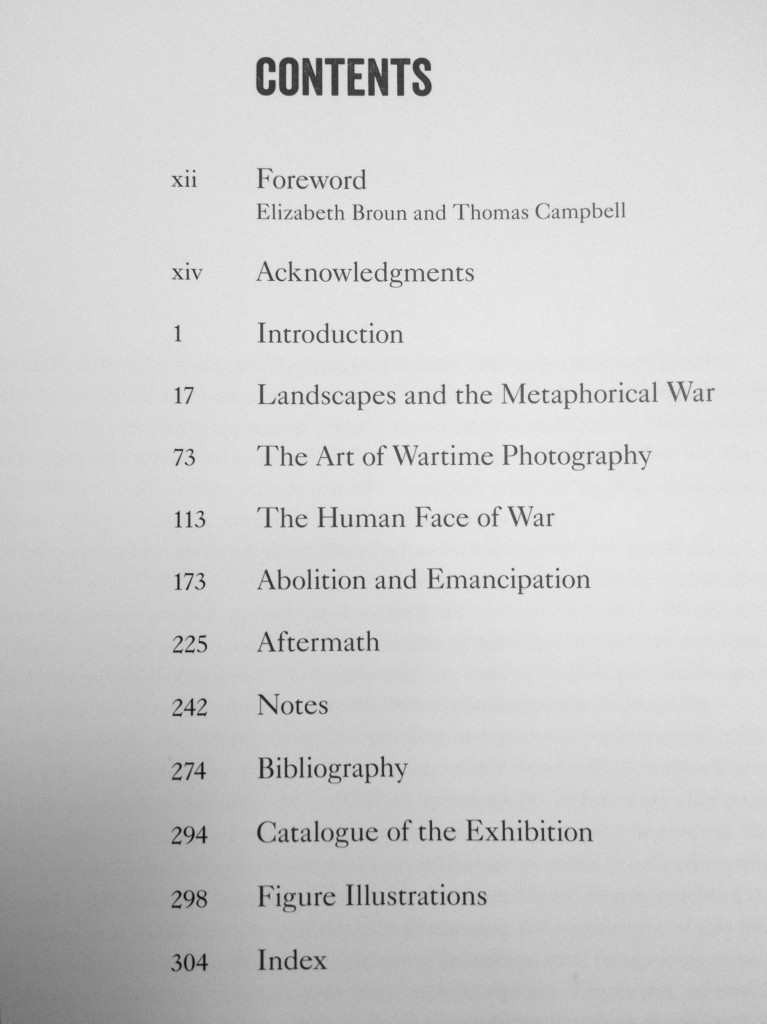

Harvey’s writing occupies pages 1 through 241 of this large book. Each generous page measures 12 1/2 by 9 15/16 inches, allowing double-column formatting of the text and providing a broad field for its many illustrations, most prominently the 77 paintings and photographs that form the exhibition. Harvey’s prose is wonderfully clear, a pleasure to dip into, blessedly free of academic jargon and devoid of esoteric pleading. She unleashes a seemingly inexhaustible supply of essential facts and observations without halting the forward momentum of her narrative and argument. This is no mean feat.

It is a pleasure to follow the author as she conscientiously uncovers layers of meaning in each of the featured paintings and photographs. Among the pieces closely analyzed are thirteen Civil War related paintings by Winslow Homer, an artist who will grow larger in your estimation thanks to the findings of Harvey’s eye and mind. She unfurls a mini-essay on each of these works, and her enthusiasm cannot help but inspire your own looking at art. If you’re fortunate enough to have access to the exhibition, as I was, this book is an enlightening spur to engagement.

.

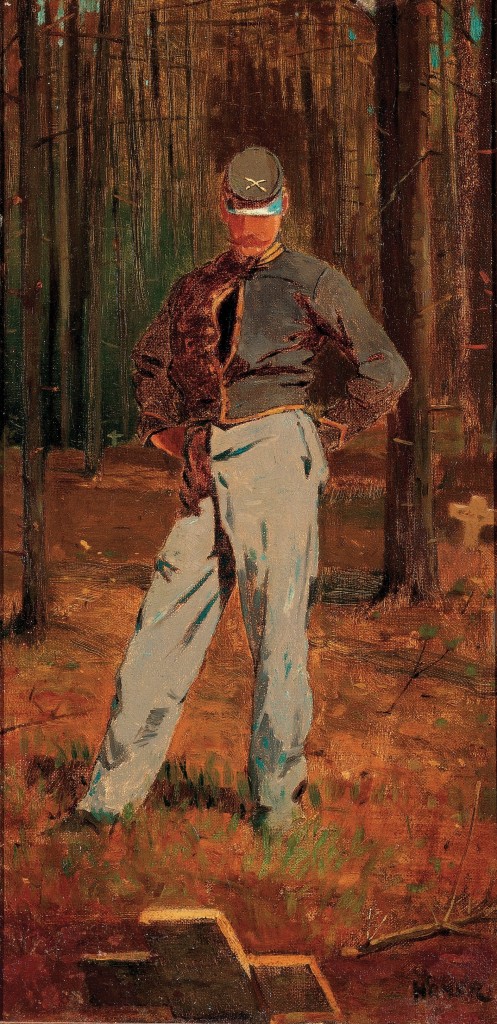

During my tour of the exhibition at the Smithsonian I spent several reflective minutes in front of Homer’s Trooper Meditating Beside a Grave, a small work (just 16 1/8 by 8 inches) that Harvey discusses on page 167.

.

.

While standing before it at the Smithsonian, I noticed two aspects of the painting not touched upon by Harvey — two understated features that will slowly surrender meaning to the patient viewer. The first is Homer’s treatment of the trooper’s stance. The artist’s depiction of feet or shoes, the natural terminus of the long-legged figure, is ambiguous, replaced with brushstrokes that create a seamless transition between the human body and the field of the dead. The vector of this transition is uncertain. Is the figure emerging from the earth . . . or subsiding into it? The second stunning detail is the trooper’s jacket whose middle buttons are opened. To a viewer this initially reads as a split in an otherwise closed seam, a way for the proudly uniformed trooper to cool himself on a warm day. Then the literal reading gives way to an alternative view, seeing a gash in his torso that opens up to reveal darkness. Homer renders this void in pure black pigment, blacker than any other application of black elsewhere on the canvas. Call it an exposure of the darkness of the heart, or the heart of darkness. We see a figure, eyeless, hollow, soulless: Death.

Each new encounter I have with Homer reinforces my belief that transition is the essential theme of his work. And how could it be otherwise for a contemplative artist whose career was birthed by the Civil War? If the vicissitudes of transition are encoded in Homer’s best work, the complementary theme of connections is of nearly equal importance. Not the least of the linkages Homer carefully constructs is that of viewer to painting. Consider this:

In a museum I stand in quiet reflection before a painting that depicts a man standing in quiet reflection before a grave. The grave is marked by a simple wooden cross. From the soldier’s perspective that cross is tilted back, as if responding directly to his gaze. It is easy for me, the viewer, to imagine the unseen face of the cross as a mirror, reflecting back to the man his own face. It is a face I study, with trepidation, for revelation.

.

The book, “The Civil War and American Art,” contains a feast of documentation. This includes a section of Notes (32 pages); a Bibliography of over 300 sources and references (20 pages); a Catalog listing the 77 works featured in the Exhibition; and a list of the 123 Figure Illustrations found throughout this beautifully designed book. A helpful Index rounds out the volume.

If I have any quibble it is that its reproductions sometimes fall short. Especially is this so with the many images captured by the early photographers Alexander Gardner, Matthew Brady, George N. Barnard and others which are reproduced in the chapter devoted to The Art of Wartime Photography. They have a denatured look on the page, in contrast to the original source albumin prints in the exhibition which possess a life and death immediacy.

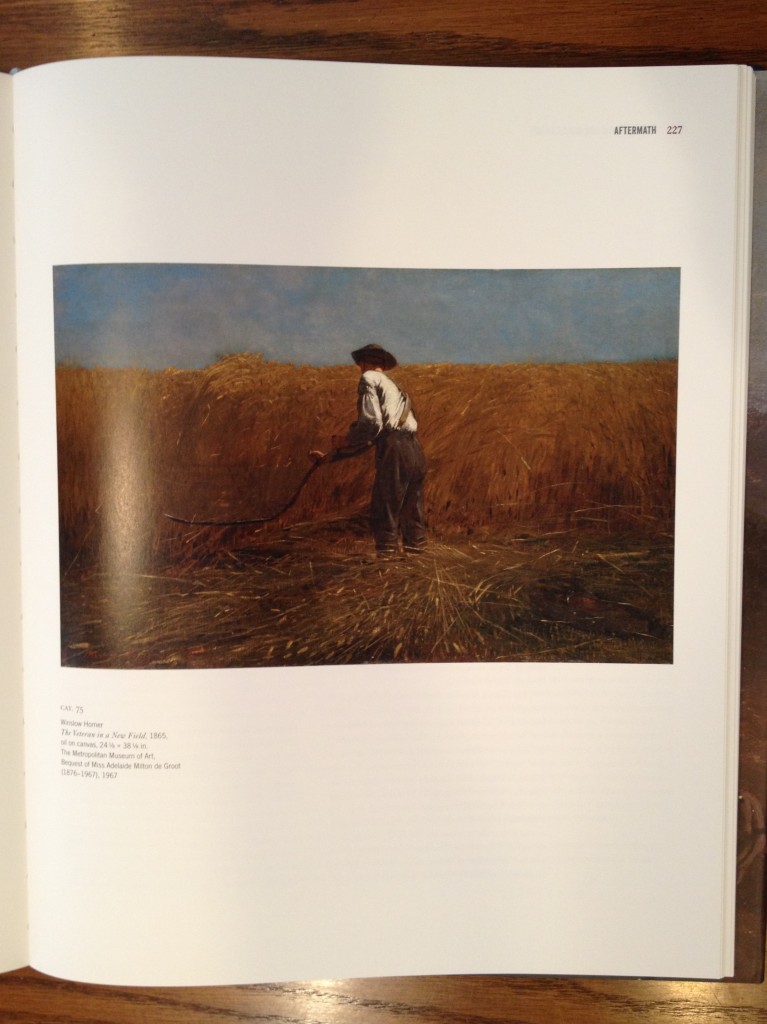

A similar deficiency-of-the-derivative occurs in the reproduction of Homer’s The Veteran in a New Field (1865). Harvey’s discussion of the painting (at pp. 225-229) mentions its “autobiographical quality,” and she specifically focuses on the former soldier’s war-issued canteen and jacket resting on the ground in the lower right corner. Here is a photo I took of page 227 on which the painting is reproduced.

.

.

A close-up shot of the lower right corner is unrevealing.

.

.

What’s not visible because of the book’s low-resolution reproduction, is a critical detail: the initials “WH” inscribed on the veteran’s canteen. This detail is best appreciated, of course, if you are in the presence of the painting itself and are able to move in for a closer look. At the end of the exhibition’s tour, The Veteran in a New Field will return to its permanent home as a treasure of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recently renovated wing devoted to American Art. In the meantime, you can catch a glimpse of the “WH” inscription thanks to the Met’s online image of the painting (click on the “fullscreen” option and zoom in). Here’s a screen capture of the jacket and canteen.

.

.

.

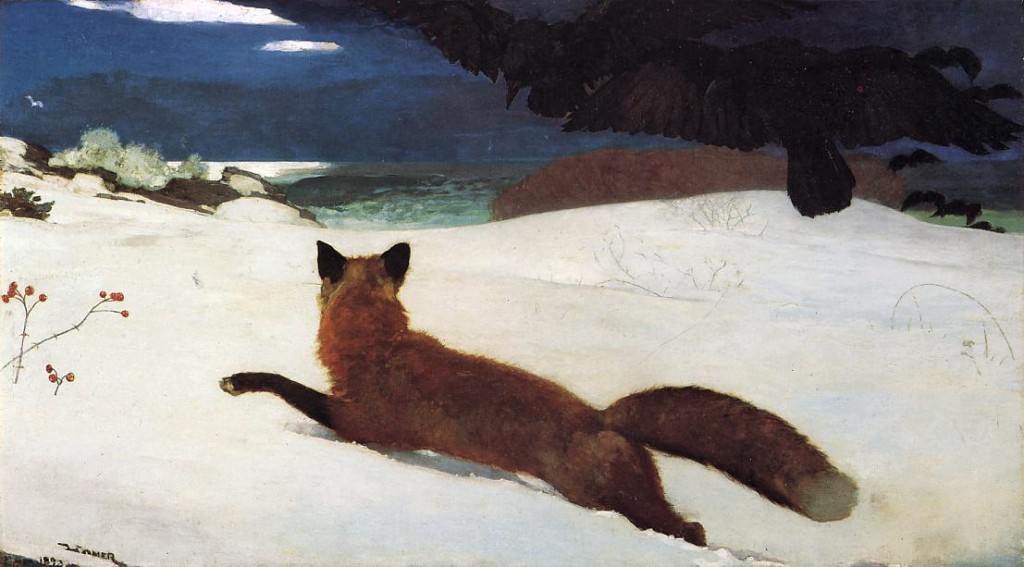

Unlike Richard Estes (or, in a different medium, Alfred Hitchcock) who plants his name (or himself) in his work as an act of whimsy, Homer sometimes does so for a meaningful reason. Most poignantly this occurs in my favorite Homer painting, The Fox Hunt, 1893 (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), where in the lower left corner of the painting his signature is immobilized by the drifting snow, echoing the pose and plight of the fox. Note also how the fox, just as the war veteran three decades before, turns his body to face away from us as he confronts a new kind of challenge on a potentially exhausting field.

.

.

.

On a playful note, another example of Homer’s look-at-me urge is to be found in a wood engraving, The Beach at Long Branch, published in Appleton’s Journal, August 21, 1869 (click on the image to enlarge). Here three young women stand wondering, Who is WH? What I myself wonder is whether Homer is alluding to the Judgement of Paris episode in Greek myth. Is he pulling a tongue-in-cheek reversal on that story, assigning to the most comely of the three young women the role of selecting . . . Mr. W.H. himself ?

.

.

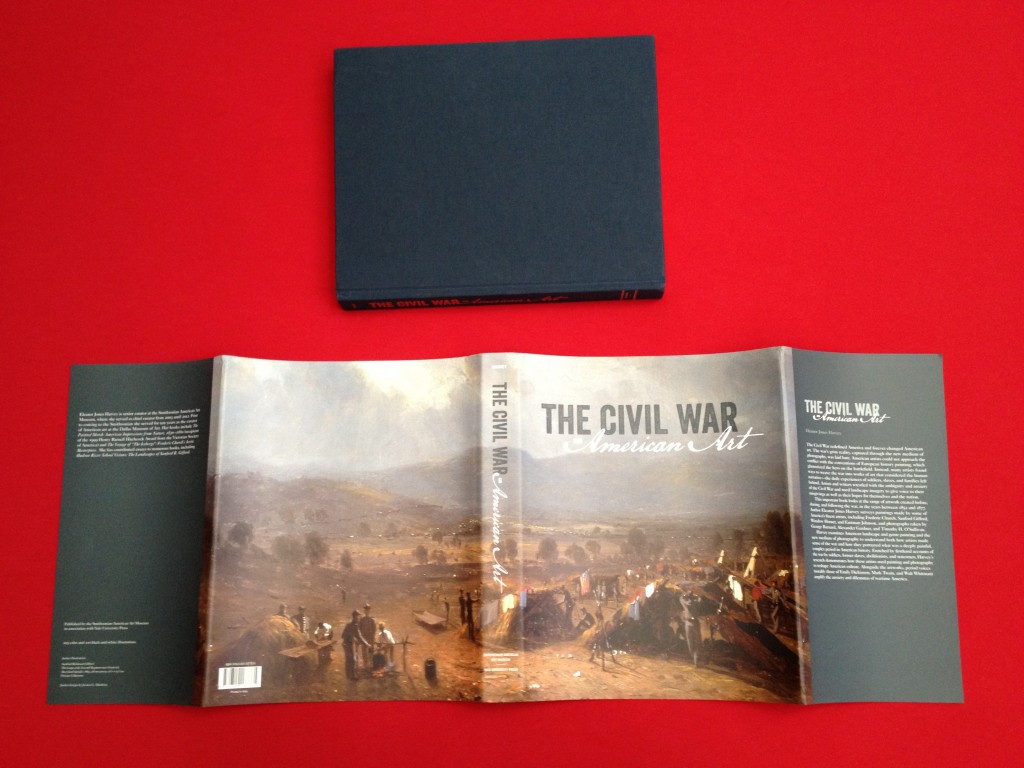

“The Civil War and American Art” is a publication of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in association with Yale University Press. To get a sense of the book’s design, you can view the first 18 pages on Scribd.com. Some additional photos of my copy prove the values that guided its production.

.

.

.

.

.

____________________________________________________________________

NOTES and further observations

1. An abbreviated version of this book review appears on Amazon.com, here.

2. The photograph of Trooper Meditating Beside a Grave in this post is the Announcement Image for a 2009 exhibition at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens (Memphis) and the Katonah Museum of Art, “Bold, Cautious, True: Walt Whitman and American Art of the Civil War Era,” a show organized by Kevin Sharp which explored ground similar to that of “The Civil War and American Art.” Additional information about that exhibit is available here, here and here.

3. Faith Barrett, in her recently published “To Fight Aloud is Very Brave,” argues that poetry also had an important role in defining national identity: “Civil War poetry changed the way Americans understand their relationship to the nation.” A November 2012 interview with Barrett can be read on the Poetry Foundation’s website , here.

4. A new installation of American art at the Detroit Institute of Arts “explores the themes of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln and the abolition of slavery.” The works in the small exhibition are part of the permanent collection galleries in the Richard A.Manoogian Wing of American art. Among the paintings is this 1861 still life, Patriotic Bouquet, by George Henry Hall.

.

.

5. On the subject of communication by metaphor, in a previous blog post I argued that still life paintings — no less than landscape and genre paintings — may encode responses to the Civil War.

6. Three years after he painted The Veteran in a New Field, Homer once again included himself in Artists Sketching in the White Mountains. The renewed artist has returned to his natural field. Homer’s back is turned away from us; he is intent on work. In a corner of the canvas, instead of finding a discarded canteen or jacket we now see a large case for the tools of the artist’s trade (visible in the detail, below). That is where Homer proudly affixes his signature.

.

.