.

.

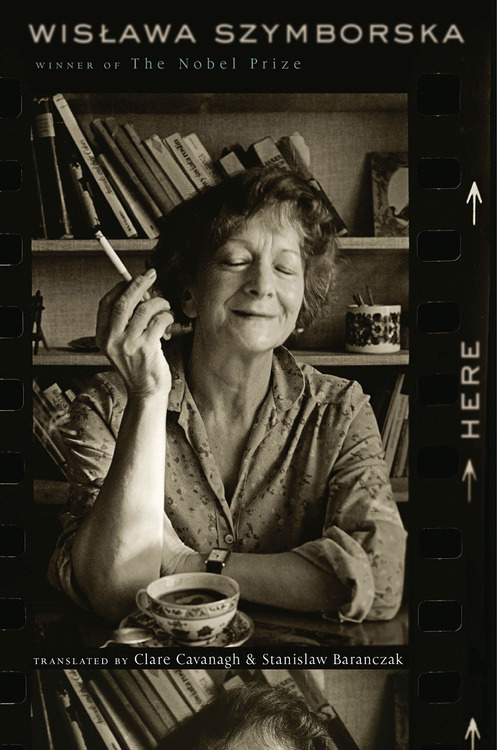

The slimmest of slim volumes of poetry, “Here” by Wislawa Szymborska contains 27 pieces for our delectation. The page count is 84, half filled with the poems in the original Polish language and half in fine translations by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak. The book was published in English just two years prior to the poet’s death at age 88 in 2012.

The writer and critic Adam Gopnik says the effect of a typical Szymborska poem is like encountering a “happy collaboration between Ogden Nash and Emily Dickinson.” Gopnik’s one word for her work is “charming.”

Through the lens of “Here” I see things differently. Although consistent with her body of work, there’s something especially attractive about these late-in-life poems. The word I myself would attach to the dominant strain in these poems is “whimsical” — playfully quaint and fanciful, especially in an appealing way. In choosing that word I also have in mind the phenomena of “whims,” those odd ideas that take over the brain and imagination very suddenly.

So Szymborska begins a poem with the question, “Me — a teenager?” and speculates what it would be like to meet her own seventy-year-younger self. (For a similar conceit, deftly executed, check out the YouTube video, here.) Then she begins another poem by blurting out, “Why not, let’s take the Foraminifera” — and proceeds to wonder whether those tiny limestone-shelled sea creatures were/are, ultimately, dead/alive. Later, confident that nothing’s lost by revealing the name of the game, she titles a new poem, “Thoughts That Visit Me On Busy Streets.”

Szymborska and Frank O’Hara could have been pals.

This may sound odd, but instead of Nash and Dickinson, the voice I hear in “Here” is a kindred spirit to the sharpest of our contemporary stand-up comedians, the men and women who mix biting social/political commentary with quotidian observational humor, acolytes of the late George Carlin, not just on subjects of pain, death, and war, but in the category of material Carlin called “the little world.”

Among Szymborska’s favorite words are “astonish” and its variants, applied to this world, this life.

Astonishments are what she itemizes in the poem whose title she also attached to the volume as a whole: “Here.” One of its 51 lines is a neat summary of the whole poem: “Life on Earth is quite a bargain.” Like a Philadelphia attorney she argues the case point by point. Her brief includes this deadpan observation —

.

“Like nowhere else, or almost nowhere,

you’re given your own torso here,

equipped with the accessories required

for adding your own children to the rest.

Not to mention arms, legs, and astounded head.”

.

The American comic and actor Louis C.K. occupies the same ground, albeit more profanely. Here’s an observation he makes in his 2013 comedy album. “Oh My God,” —

.

“I like life. I like it. I feel that even if it ends up being short, I got lucky to have it.

Because life is an amazing gift when you think about what you get with a basic life.

Here’s your boiler-plate deal with life — this is “basic cable, what you get when you get life:

You get to be on earth.

First of all, Oh my God, what a location! …

You get to [#%@!]; that’s part of the deal.

Where else are you going to get that deal?”

.

By the end of her life Szymborska had armed herself with a ready answer to the rude question many interviewers posed: Why have you written so few poems? She replied:

“A poem written in the evening is read again in the morning. It does not always survive.”

Now, once you’ve read “Here” or another collection of her work, your perception is likely change in a way that allows you to understand how Szymborskiac this seemingly tossed-off response is. It reveals one writer’s writing habits, of course. But listen to it again. How much contingency it contains, how much a reminder of love (passion expecting to last … ) and death ( … yet only to disappear).

.

[Note: A version of this review appears on Amazon, here.]