.

.

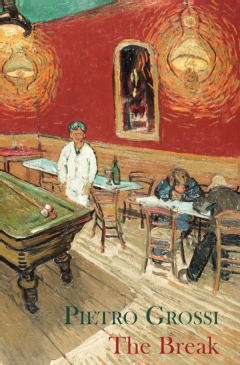

THE BREAK, a novel originally published in Italian (“L’Acchito,” 2007), is the second book by Pietro Grossi to be translated into English and made available in the United States. It follows the release of a collection of three novellas, FISTS (“Pugni,” 2006), from the same publisher, Pushkin Press, in an equally handsome paperback edition.

FISTS impressed me mightily (see review here). Its high point is the opening story which traces the coming of age of a young amateur fighter. The arc of that simple tale is reenacted on a larger canvas in THE BREAK. A stone-layer named Dino, still in his twenties and leading an uneventful life in the rural town of his forebears, suddenly must deal with two unsettling developments: his wife is pregnant and his old job disappears. He seizes on the idea of perfecting his talents at billiards (the form of the sport featured here is known as Italian billiards or Italian five-pins). He embarks on contests that will lead to a further maturity.

This is a beautifully realized novel in which Grossi fulfills the promise of his initial work.

Laying down a single word — craftsmanship — is the best way I can think of to describe the source of strength found in THE BREAK. It’s not a coincidence that Grossi spent two years of his apprenticeship period studying at the Holden School (La Scuola Holden) in Torino, Italy. The curriculum at that institution emphasizes mastery of narrative — storytelling in all of its guises, not just in the short story and novel, but also in the realms of radio, theater, film and web-based content.

An aside: profiles of Grossi often mention, misleadingly I believe, that he is a follower of the American writer J.D. Salinger. I find little or no evidence of Grossi imitating the American. The linking of the two writers may be nothing more than a misunderstanding (or misrepresentation) of the fact that the founders of the Holden School named it (yes) after Holden Caulfield, the unforgettable narrator of “The Catcher in the Rye”.

No one can deny the meticulous quality of Grossi’s writing. From the very first page of THE BREAK, the reader will notice the clean, fine construction of sentences and paragraphs, quickly-limned characters, and deft scene-setting, all of this well captured in Howard Curtis’ translation. Here is Dino, out on the street, sensing winter’s approach:

“The days were already drawing in. It was the beginning of that time of year when, as evening fell, people seemed to be wandering through a darkened theater.”

Grossi conveys the uncertainties Dino experiences via subtle phrases (usually disguised as ordinary descriptions) carefully positioned, piece by piece: “Dino couldn’t quite explain it”; “what the questions were he didn’t even know himself”; “maybe people had lost the habit”; “for some reason . . .”. There is a reiterated motif of how two persons’ physical closeness to each other discloses emotional information. One instance is the description of Dino as he and his wife Sofia occupy two corners of their tiny kitchen: “It had always made him feel good, being close to each other like this but slightly distant, and not talking.”

Grossi seems to know instinctively where to guide the reader and how best to do it. For example, only a few pages into the book Sofia reveals she is pregnant. The homey atmosphere Grossi creates for this initial scene is so old-fashioned your memory may naturally summon up the phrase, a woman “with child.” This thought is not unprompted, for just a few lines before the revelation Grossi had described for you the child-like nature of the parents-to-be: “They ate in silence, both sucking the soup from their spoons as softly as they could and playing their old game of trying to see shapes in the vegetables.” You have been smoothly guided to the emotional surprise: Characters, not yet fully formed adults, are about to become parents.

Less successful, because its obviousness is at odds with the subtlety of Grossi’s hand elsewhere, is the dominant metaphor of the novel — that of the billiards table and the psychological play enacted upon it. Still, this stand-in for life, fate and destiny is a seductive draw:

“Dino was here [at the billiards parlour] because he needed things to be clear and precise, to know where they were going to end, to know that there was still a piece of the world where lines and forces and movements followed exact trajectories, without frills, without flights of fancy.”

It occurs to me this description could serve equally well as Grossi’s personal credo as a writer.

The heart of the book is a love song to the pool hall and the passions unleashed there. On this ground alone, fans of the sport and fans of fictional depictions of its world (such as The Hustler) are likely to enjoy THE BREAK.

The novel’s 28 chapters average just seven pages each. This framework sets up a fade-in/fade-out rhythm that, along with other scenario-like elements, may remind you of expert film writing. However, it also points to what some readers may find to be a weakness in Grossi: his comforting conventionality. Seekers of the unconventional should steer clear. The characters and themes Grossi explores have reminded some critics of post-WWII neorealism in Italian cinema, with its emphasis on real lives and quiet tiny moments. I would add there are affinities to the kitchen-sink dramas of British and American playwrights of the 1950s (“Look Back in Anger”; “Marty”) that explored what Paddy Chayefsky called “the marvelous world of the ordinary.”

.

A version of this review is posted on Amazon, here.