.

.

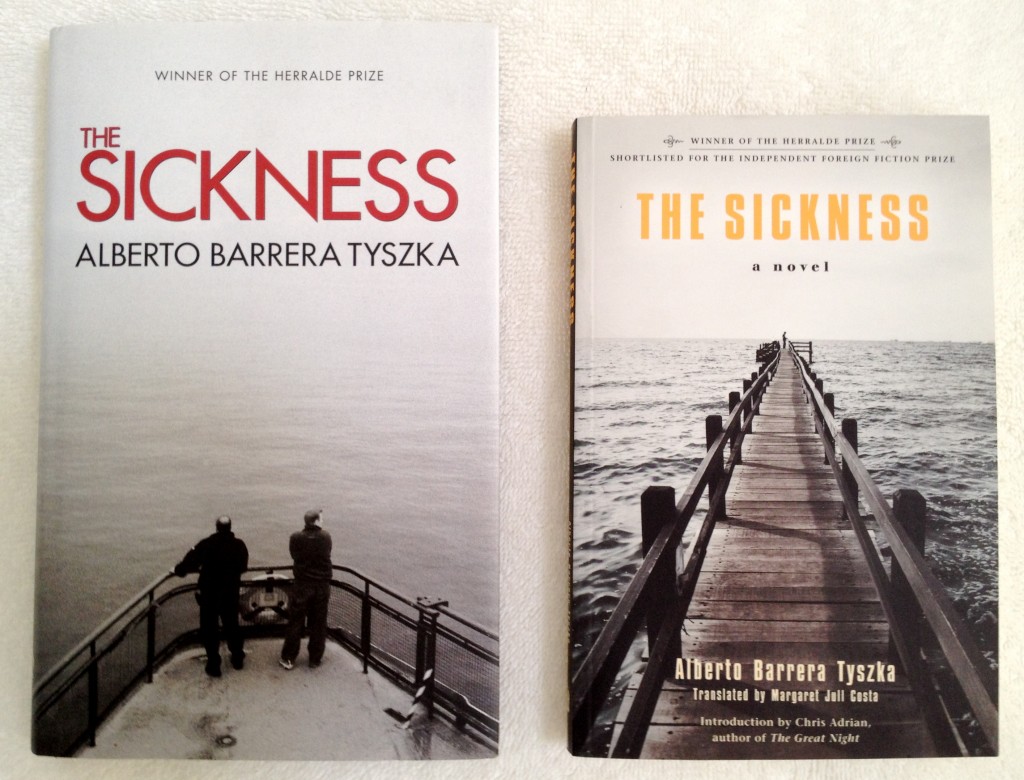

A novel searing in emotional power that will be felt especially by readers who have lost a parent to a difficult illness, THE SICKNESS qualifies as a necessary book. It is the most accomplished piece of literature I’ve read recently, and unquestionably the most moving.

Alberto Barrera Tyszka’s formidable achievement starts with a simple formal structure — two intertwining storylines that play out over the course of a month or so, involving a handful of people living in contemporary Caracas, Venezuela. The primary focus is on Dr. Andres Miranda and his relationship with his sixty-nine-year-old father. In the opening pages the son learns his father has an aggressive form of cancer that will kill him in only a few weeks’ time. (Their reticent love may remind you of the father-son relationship in Per Petterson’s Out Stealing Horses: A Novel). A secondary story traces the emotional entanglement of the doctor’s secretary with a hypochondriac patient, charted through a fevered exchange of email messages.

I’m hoping THE SICKNESS receives the attention of careful critical reviews in places that allow for expansive analysis. So finely packed with incident and insight is this novel, so expertly orchestrated are its emotional revelations, and so sure-footed is the author’s blending of erudition and raw truths, that you will be caught in its influence long after reading its final pages. (The American novelist Chris Adrian, who supplies a short Introduction, confesses he was at first afraid to open the book with its wrenching report of terminal illness; then, having read it, he found himself eager to read it again.) There is so much to talk about! This novel is an ideal selection for a book club discussion.

Among Tyszka’s wonderful touches are his aphoristic observations, nonchalantly released into the flow of the narrative. These are usually serious and relate to the medical world, though not always: “Blood is a terrible gossip.” “Sickness is a form of disloyalty, an unacceptable infidelity.” “Why do we find it so hard to accept that life is pure chance?” In old age “there are no more deadlines, there is only the present.” “There are some people who only read in waiting rooms.” “Adolescence is the most unclassifiable of joys.” “Reality is always different when you’re taking a shower.”

And consider this Zen-like statement:

“Tears are very unliterary: they have no form.”

Throughout the novel the generous Tyszka also pays homage to the thoughts of others who’ve traveled the same terrain of illness, pain and death. Among them are Chekhov; Celine; Robert Burton, who wrote “The Anatomy of Melancholy” (1621); Susan Sontag, who observed there are two kingdoms, sickness and health; William Carlos Williams, who wrote that the doctor “must watch the patient’s mind as it watches him, distrusting him”; and Michel Foucault, who said that, “viewed from the experience of death, illness can be seen as a function of life.”

The book asks — and answers — the final question: What is the best way to say goodbye to life?

Other reviewers who are better qualified to judge the translation have praised Margaret Jull Costa.

In my photo, above, the U.K. edition (hardback) is on left, U.S. edition (paperback) on right. Depicting what appears to be a father and son at the prow of a ferry boat is appropriate as it directly relates to two scenes in the novel. The photo of a pier extending into the sea with a lone figure at its apex is an example of poetic license.

.