.

.

What’s this children’s book (published in 1993) all about? The Library of Congress Cataloguing-In Data Summary found on the book’s Copyright page dispatches the plot in one sentence:

“A very messy princess in a very tidy royal family has the opportunity to prove that there are advantages to not being neat.”

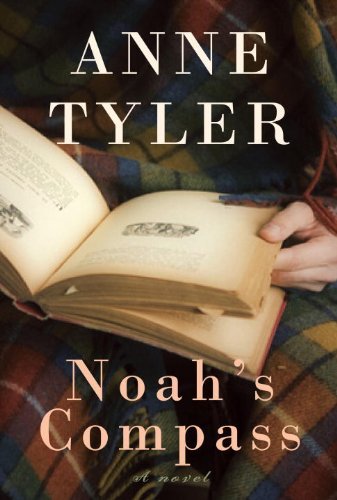

At the risk of coming across as a fuddy-duddy, I will point out that, amid the steady charms of Tumble Tower‘s story line (written by novelist supreme Anne Tyler) and the flow of its abundant illustrations (finely crafted by Tyler’s daughter Mitra Modarressi), some wrong notes occur.

A minor one is this: I’m not sure many boys would agree to don their sisters’ pajamas, as the little brother, Prince Thomas the Tidy, does here without a squabble.

A potentially important note is this: If you and your child still struggle over cleanliness issues — by which I mean matters of basic sanitation — it might be best to avoid this book, or at least be prepared to engage in lots of explaining, especially if your child absorbs messages in a literal fashion. In real life there is “cute-messy” and there is, well, let’s call it “dangerous-messy.” Here the significance of that distinction is mostly avoided.

Princess Molly’s bed is “all lumpy and knobby with half-finished books.” Oh? Are her bed sheets never changed? The princess is very happy to consume an old, half-eaten candy bar she finds hidden beneath a chair cushion. Hmmm . . . . is this, and the other abandoned food in the room, still fit to eat? The royal cat has given birth to six kittens amid the floor-tossed clothing. Is Molly’s bedroom this really the best location to this activity? The room is a minefield of toys and whatnot, every square inch of its floor covered with objects. Just how far do you suppose a parent, called to this child’s room in the night, would be able to walk across that floor without coming to personal harm? How soon would we hear screamed some very un-Tyleresque four letter words? Modarressi and Tyler do not see it as their job to suggest to the young reader/listener that there is anything amiss in this. It’s left largely to you, the parental reader, to encourage your child to think things out.

Which is, of course, as it should be.

Aside from these nits, the book is great fun to read.

Half of the pleasure of reading a good children’s book written by a great novelist comes from recognizing traces of the author’s adult preoccupations. And so it was fun for one Anne Tyler fan (me) to read “Tumble Tower.” I can see why Tyler was drawn to Messy Molly. Here was a chance to add a princess (royalty: talk about a quirky line of work!) from a family tagged with funny names (Molly is the daughter of King Clement the Clean and Queen Nellie the Neat) to the author’s growing list of protagonists whose personal space is full of clutter. Tyler views messiness, both the emotional and the material kind, as an inescapable condition of life. The tension between the comforts of clutter and a yearning to break free of it has been a fount of humor in most of her novels.

Veteran readers of Tyler know that when a clutterer meets an unclutterer, sparks fly. There’s Martine, the Rent-a-Back crew member in “A Patchwork Planet, who with rough efficiency de-clutters the homes of elderly and sometimes resistant pack-rats. Recall unhappy mom Delia Grinstead in “Ladder of Years” who decides to just up and leave her family. Is that ultimate act of uncluttering one’s life, or no? Remember, too, the title character in Morgan’s Passing, who instructs his daughter in the same stern manner as King Clement the Clean: “You would be surprised at how many things are non-essential. Throw everything away. All of it! Simplify!”

The Summer 1992 edition of The Virginia Quarterly Review contained an essay on Anne Tyler written by Patricia Rowe Willrich, who for several years engaged in a correspondence and literary friendship with the reclusive author. Willrich relates that, on a continuum from messy to neat, Tyler is not a saver, let alone a hoarder: “Her old stone home in Baltimore is organized and spare. The living room and dining room, with oriental rugs and a few pieces of furniture, are uncluttered. Floor to ceiling bookcases are full, but neatly organized. When someone gives Tyler a new book, she gives one away.”

So there you have it: Anne Tyler is Queen Nellie the Neat.

Final note: A dozen years after releasing “Tumble Tower” in 1993, the mother-daughter team of Tyler and Modarressi reunited to produce their second children’s book, Timothy Tugbottom Says No!.

.

A version of this review appears on Amazon, here.