.

In 2017 I was able to place a few American artworks into the collections of five museums.

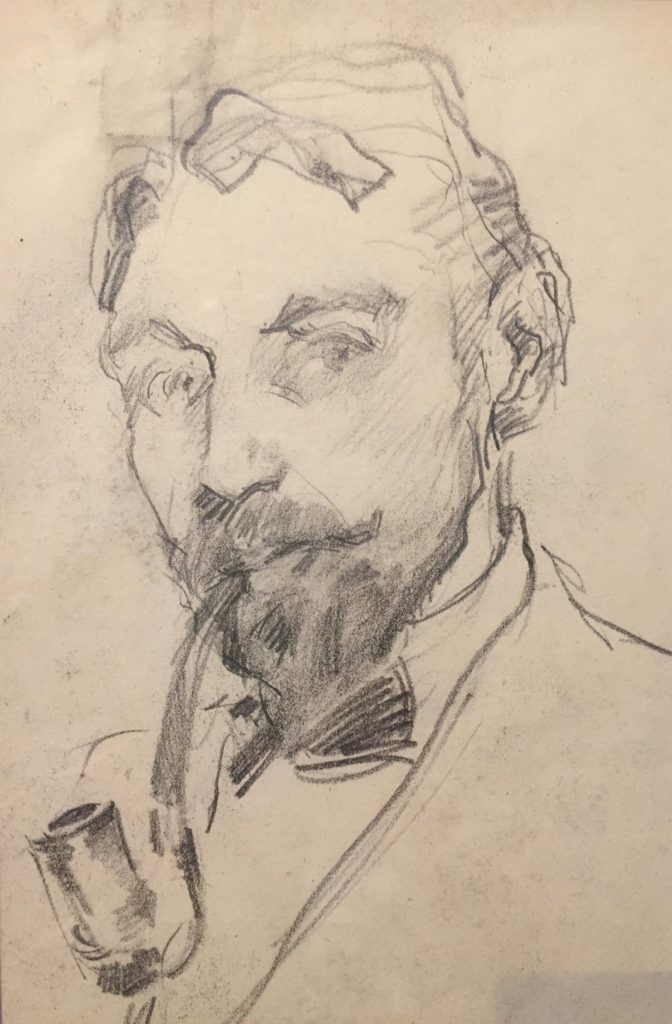

1. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts accepted my gift of a pencil drawing by Arthur B. Carles (1882-1952) that I had recently spotted and bought at auction. Carles was an early 20th century Philadelphia modernist who studied and later briefly taught at the Pennsylvania Academy. This small drawing (9.5″ x 5″), stamped on the verso with his estate stamp, is a self-portrait. The relatively young artist presents himself as a man of confident demeanor. His expression is open, inquisitive, wry, and ever-observant.

.

.

2. The Woodmere Art Museum, also located in my hometown of Philadelphia, accepted into its collection two paintings. Each is a 19th century work with a Philadelphia connection. I had the Woodmere museum specifically in mind when I came across them at an auction sale early in 2017. I was familiar with Museum’s motto: “Telling the Story of Philadelphia’s Art and Artists,” and thought these would fit right in.

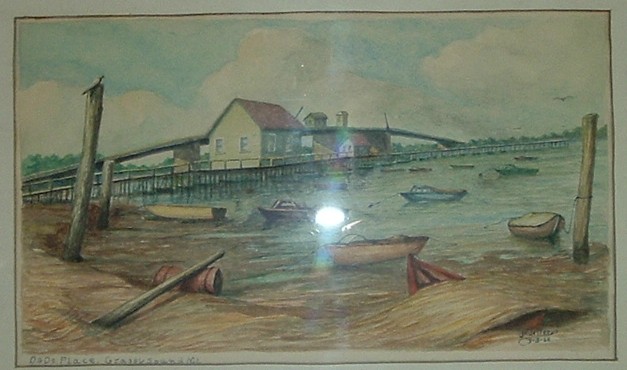

The first work is by William Thompson Russell Smith (1812-1896. It is titled on the verso, “Rockhill, Branchtown [Philadelphia]” Dating from 1844, this an oil on canvas on board, 16″ by 23 3/4 inches in size. A 19th-century inscription on the verso indicates the house and grounds depicted were Russell Smith’s home from 1840 to 1854. Additional labels attached to the reverse show its provenance includes two commercial galleries, Alexander Gallery and Questroyal Fine Arts, both located in New York City. The provenance very likely includes the Cooley Gallery, as this painting appears to be the same work described in a fact sheet prepared by that Connecticut dealer.

The mother and two children who are pictured on the lawn are almost certainly the artist’s wife, Mary Priscilla Wilson, and their son and daughter — Xanthus Russell Smith born in 1839 and Mary Russell Smith born in 1842. Xanthus and Mary both became painters.

.

.

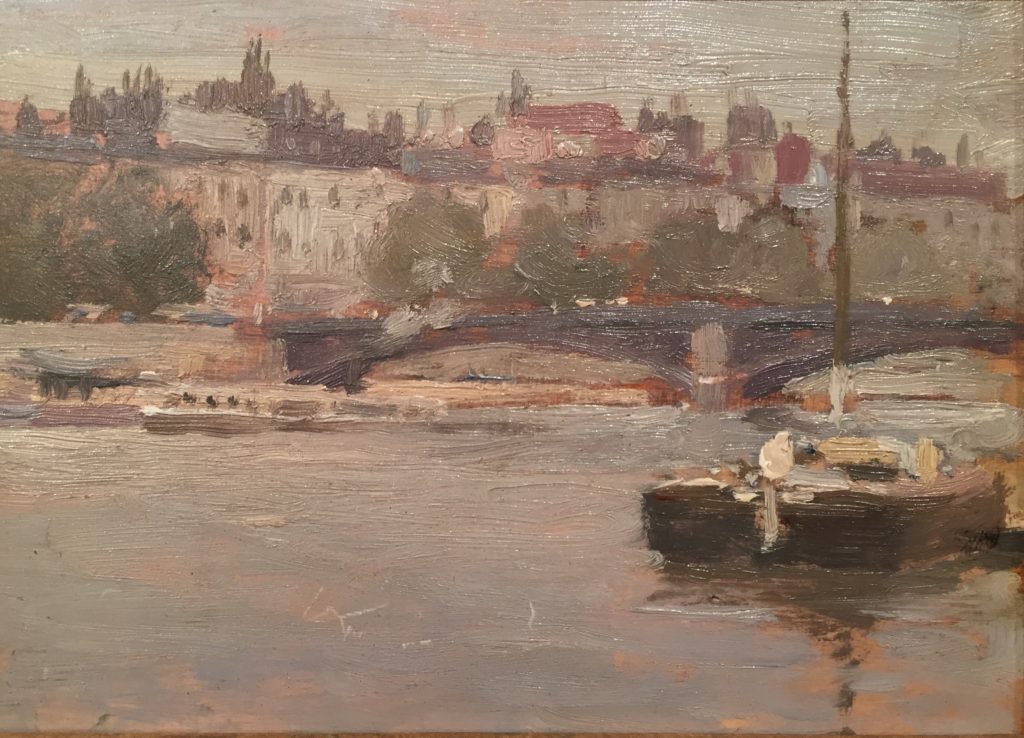

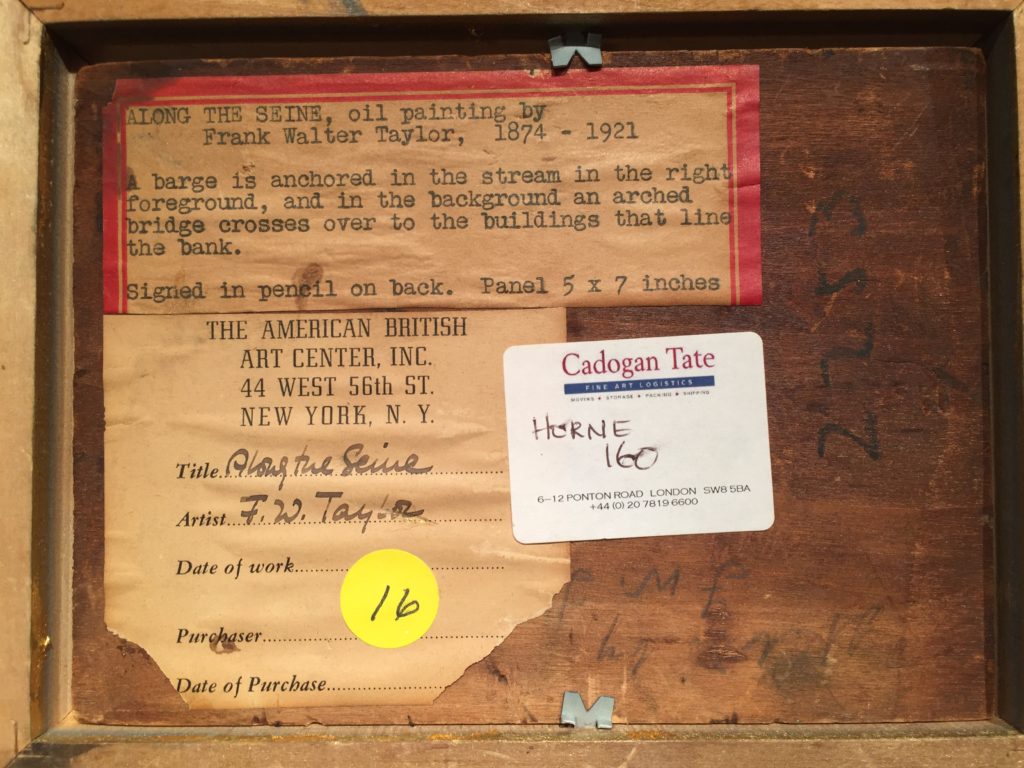

The other work accepted by the Woodmere Museum is a plein air oil sketch on wood panel by Frank Walter Taylor (1874-1921). Entitled “Along the Seine,” it dates from the late 1890s and is a mere 5″ x 7″ in size. Taylor began studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the mid-1890s, then continued his education in Paris on a traveling scholarship. In 1898 he returned to Philadelphia, where he became a prominent illustrator.

.

.

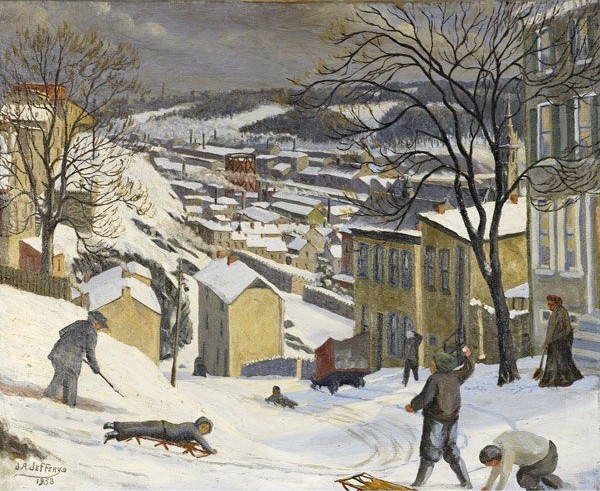

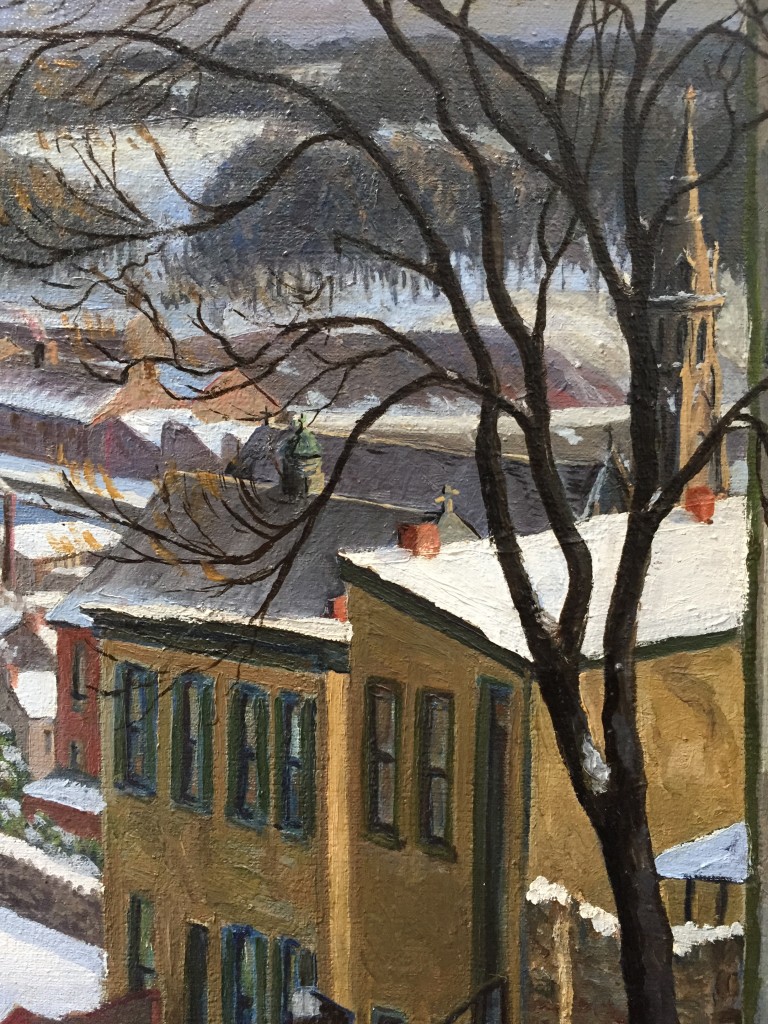

3. The Westmoreland Museum of American Art received a landscape painting of Western Pennsylvania by Norwood Hodge MacGilvary (1874-1949). Titled “The Optimist,” this oil on canvas is 25″ x 31″ and undated, although a label on the verso from the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh lists the artist’s address as “College of Fine Arts, Carnegie Tech.” — suggesting the painting dates to the period 1921-1943 when MacGilvary taught painting at that school. A brief biography of the artist can be found here. Additional photos of details of the painting are available here. The gift is reported on page 6 of the museum’s January-April 2018 Newsletter, here.

.

.

4. The American University Museum at the Katzen Art Center, in Washington DC, accepted my gift of a painting by Hilda Shapiro Thorpe (1919-2000). This untitled color block abstraction, dating from the 1960s, relates to the work of her fellow artists of the Washington Color School produced during that exciting decade. This is an oil on canvas, 48.5″ x 26,” signed by the artist in marker on the stretcher as “Hilda Shapiro”

.

.

5. Columbia University Art Collection, Avery Art Properties, accepted my gift of two paintings by artists who were active in New York City in the 1980s and 1990s.

The first is a work by Peter Nagy (American, b. 1959), artist and co-founder of Gallery Nature Morte which operated during the height of the East Village art scene in the early 1980s. Titled “Static Fades,” this oil and acrylic on canvas is 36″ x 36″.

.

.

The other painting is by Vernon (“Copy”) Berg (American, 1951-1999). An oil on canvas measuring 20 inches square, it is untitled but dated 1990 on the verso. Today, Berg is mostly known for his importance in the history of the gay liberation movement, yet his artwork deserves greater exposure and attention than it has received. A 1995 NY Times profile of the artist is available, here.

.

.

This painting is one of the few canvases completed by Berg in his final years, a period when his health and strength declined due to complications from AIDS and he shifted his attention to small drawings and watercolors. It’s a wild and interesting piece.

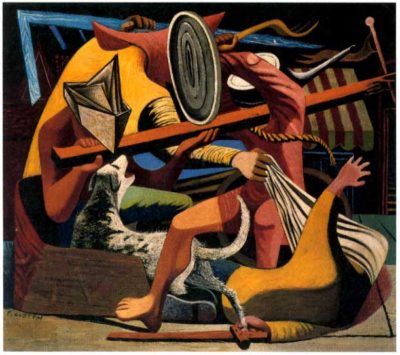

The painting appears inspired by a daydream — or a hallucination. The setting is an unfurnished interior space with a high ceiling, as found in a museum or commercial art gallery. That it may be a picture gallery is suggested by Berg’s insertion of four, incompletely-drawn black rectangles. On the left side, two largely intact rectangles, each of which cuts into a portion of the overall tumultuous activity, look like they are instruments to corral and compose a portion of the action, to create independent pictures out of a chaotic whole. The effect is similar to the way a photographer selects and circumscribes a scene through the camera’s view-finder. Or the way an artist edits a broad vista via exclusion, testing solutions by placing their hands in this configuration:

Could the painting be a commentary on the art-making process, a summary of the fraught journey that leads from an artist’s initial visualization to a final gallery exhibition of completed work? Are we looking at an imagined exhibition of Berg’s own pieces — the ones he was struggling to finish — magically come to life?

What’s certain is that the figures will not be fenced in. The painting is crowded with animated beings drawn in a cartoon fashion, similar to Berg’s rendering of cats in Cat Tango (1988, oil on canvas, 72″ x 60″), dinosaurs in Dinosaur Conversation (1990, watercolor on paper, 9″ x 7″), and two fantastic beings in A Centaur and An Angel (1993, watercolor and crayon on paper, 14.5″ x 14.5″) (three of 36 Berg artworks found here).

Some of the figures in this untitled work are grounded, others hover in mid-air where they cavort and argue and couple closely. There is discord. I’m struck by how the scene envisioned by Berg within a tilted, vertiginous space, is reminiscent of the physical interaction imagined many decades before in an early Philip Guston painting: