.

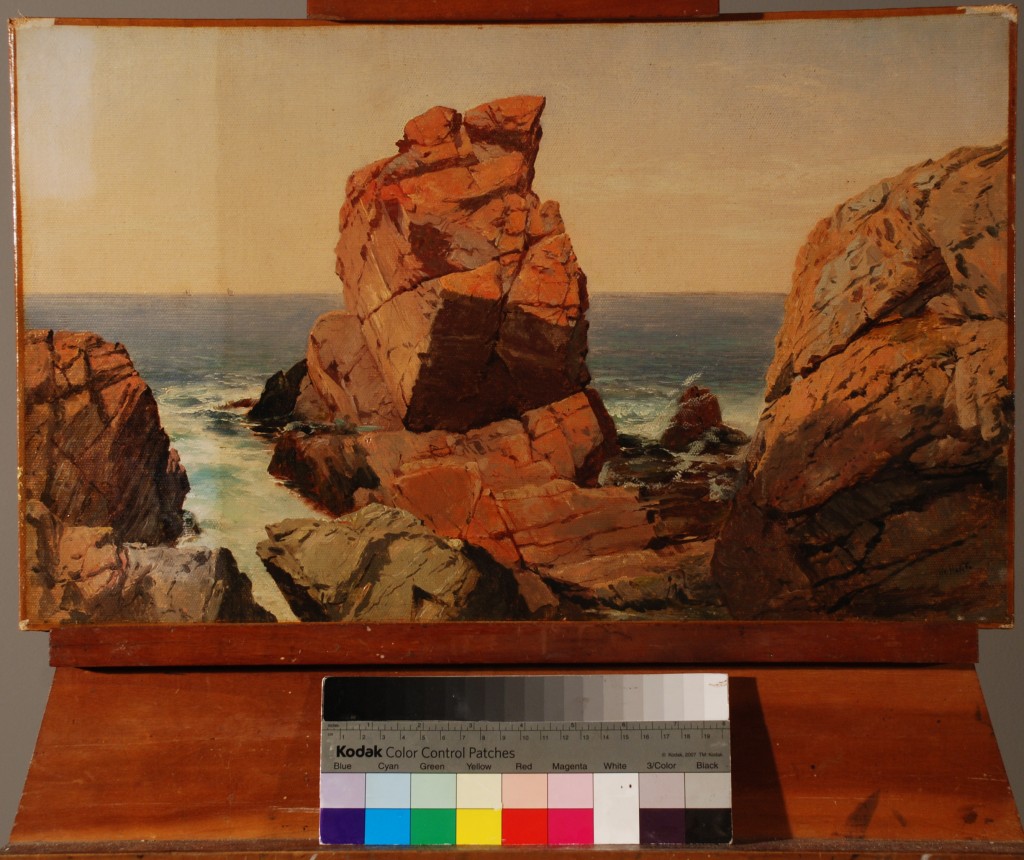

Recently I acquired a small still life painting by the 19th century American artist Edward Chalmers Leavitt (1842-1904):

.

| Still Life with Apple on a Marbletop Oil on canvas, signed lower right and dated 1862. 6.5 x 8.75 inches |

.

Depictions of apples are very common in nineteenth century American art, and it’s not hard to understand why.

The apple’s renown can be traced to decades of widespread cultivation of apple trees throughout the growing nation. Successful harvests yielded not only abundant and flavorful table fruit, but an important beverage: millions of gallons of hard cider which thirsty Americans consumed with abandon.

For a young nation still in the process of defining itself, the apple was an object poised to take on symbolic importance. The natural stages of apple production — seeds, saplings, trees, new blossoms, nourishing fruit — furnished metaphors for nation-building. And when the new nation was in need of home-grown myths, they annointed Johnny Appleseed, whose legend is substantially rooted in fact.

.

William Gropper, “Johnny Appleseed,” lithograph (another version, here)

.

Johnny Appleseed became a hero of a quintessentially American kind, as his story blends both moral and practical lessons. Likewise the humble fruit he championed. Americans saw in the apple something they were temperamentally inclined to invest with representational authority.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the apple had achieved a status approaching that of a national symbol. Twice in his journals (in 1848 and in 1851) Ralph Waldo Emerson declared the apple to be “our national fruit,” and he later voiced that same judgment without fear of contradiction in lectures devoted to “Country Life” delivered to audiences in Boston and Worcester (1858) as well as in Brooklyn (1859):

“The apple is our national fruit. In October, the country is covered with its ornamental harvest. The American sun paints itself in these glowing balls amid the green leaves, the social fruit, in which Nature has deposited every possible flavor; whole zones and climates she has concentrated into apples.”

This background adds to our understanding of Still Life with Apple on a Marbletop and the artist who painted it.

In 1862, Edward Chalmers Leavitt, a young man eager to extend his artistic reach beyond an early talent for drawing, decided to capture an apple’s essence in oil paint on canvas. This small painting may be the earliest surviving work by him, according to my research. Indeed not much is known with certainty about Leavitt’s training and early career as an artist. His first participation in an art exhibition occurred five years after Still Life with Apple on a Marbletop, when a work labeled “Fruit Piece (painting)” appeared at an exhibition sponsored by the Rhode Island Society for Domestic Industry. In his later years Leavitt achieved local prominence as the premier still life painter in the city of Providence, churning out grandiose and meticulously detailed compositions reflecting America’s material prosperity at the end of the century. These later commercial works, designed for an upper middle class market, are a long way away from his early apple.

A single apple on a shelf: what could be simpler, more humble, more innocent?

.

.

.

But look closer. Doesn’t this begin to look like more than the commonly encountered image of an apple? I think the answer is yes. Many a curious thing is to be found in Leavitt’s depiction of America’s fruit. Some things extraneous. Some things pointing beyond the literal, beyond the space the artist constructed to house his apple. Perhaps something with a personal meaning.

What I see in the painting now set before me is this:

Here, in a simple depiction of an apple on a marble shelf, the artist has encoded the state of the nation in 1862.

I interpret the painting as a representation of the country as seen through the eyes of a young man during the eventful year of 1862. Yes, I’m engaging in some speculation here. I may never find confirmation of my premise. But what I do have in hand already are two things: a tantalizing biographical fact, and the evidence of the painting itself.

Here is the interesting fact: Edward Chalmers Leavitt, born and educated in Providence, Rhode Island, decided at the age of 19, at the outbreak of the Civil War, to volunteer to serve the Union cause. Exactly when in 1862 he painted Apple on a Marble Tabletop may never be determined. But there is little doubt in my mind that throughout the months of 1862, Leavitt, like other young men of his time and place, must have followed intently every scrap of news and rumor that came his way about the campaigns and battles of the war. That second year of the Civil War saw the further terrible sundering of our nation. Blood was spilled on the battlefield; tears were spilled on the homefront.

The painting itself — its iconography — is intriguing. My reason to believe Leavitt had a higher aspiration for his painted apple, that he intended this apple as a commentary on contemporary events, is grounded in three elements of the picture. These details telegraph a message.

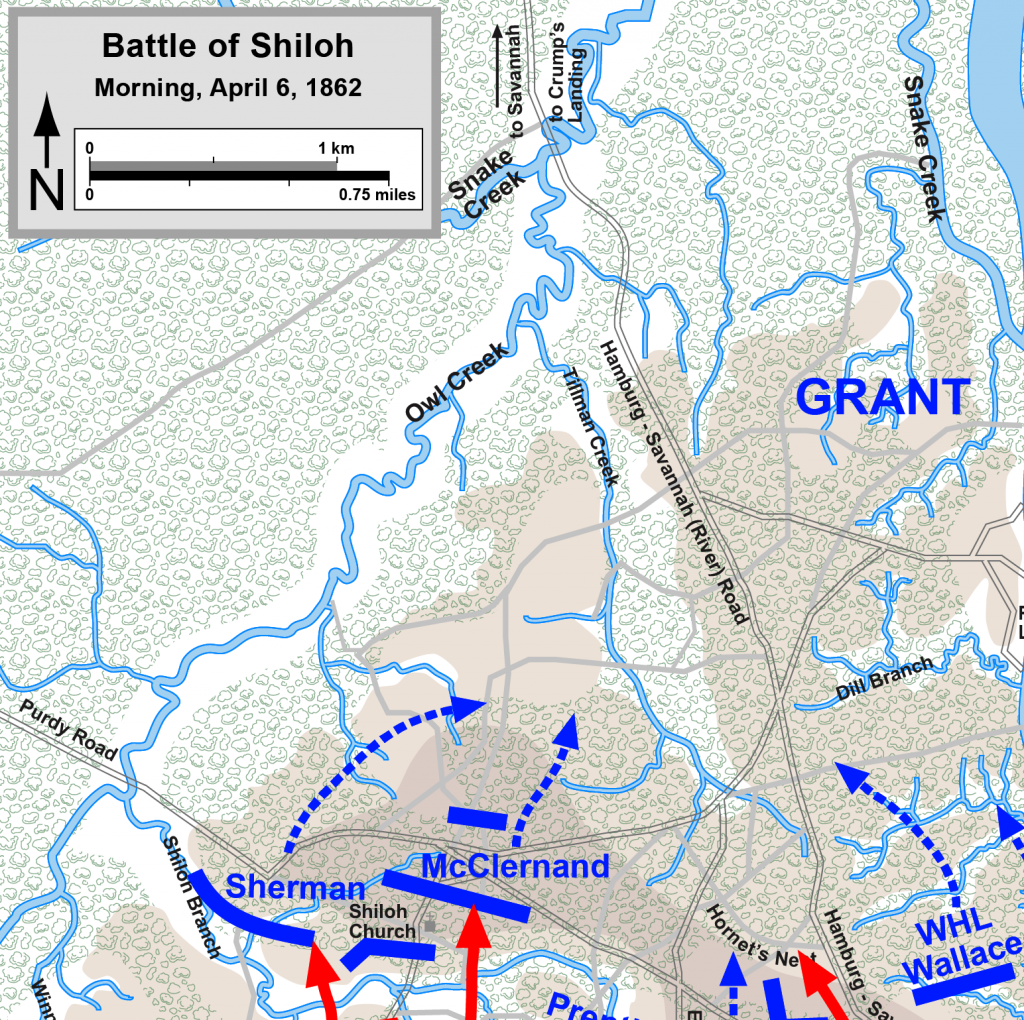

1. The geography of battle

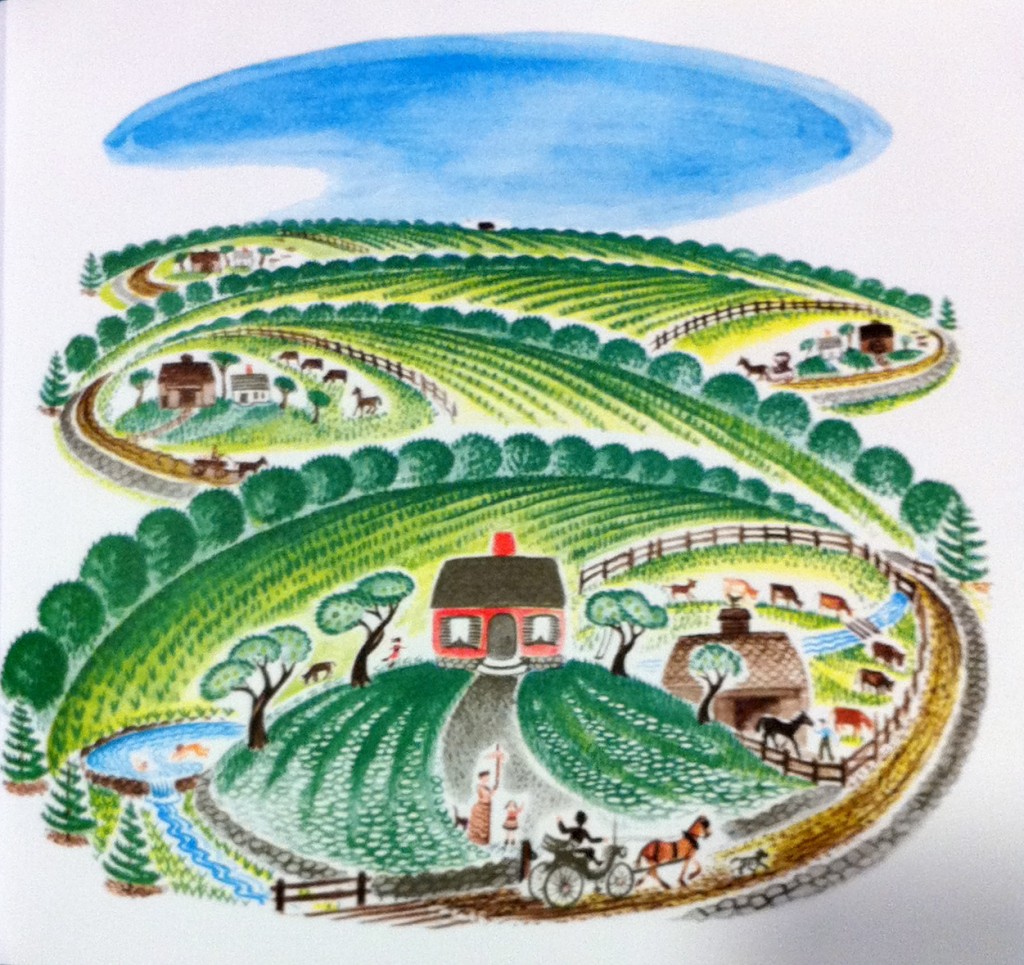

First there is the matter of how Leavitt depicts the physical setting the apple occupies. Within a very small format (just 6 1/2 by 8 3/4 inches) the artist has created a narrow and shallow display space. On reflection, however, this space broadens out to encompass a larger space. This in turn allows the apple to assume a larger meaning. What did Leavitt do to transform the space?

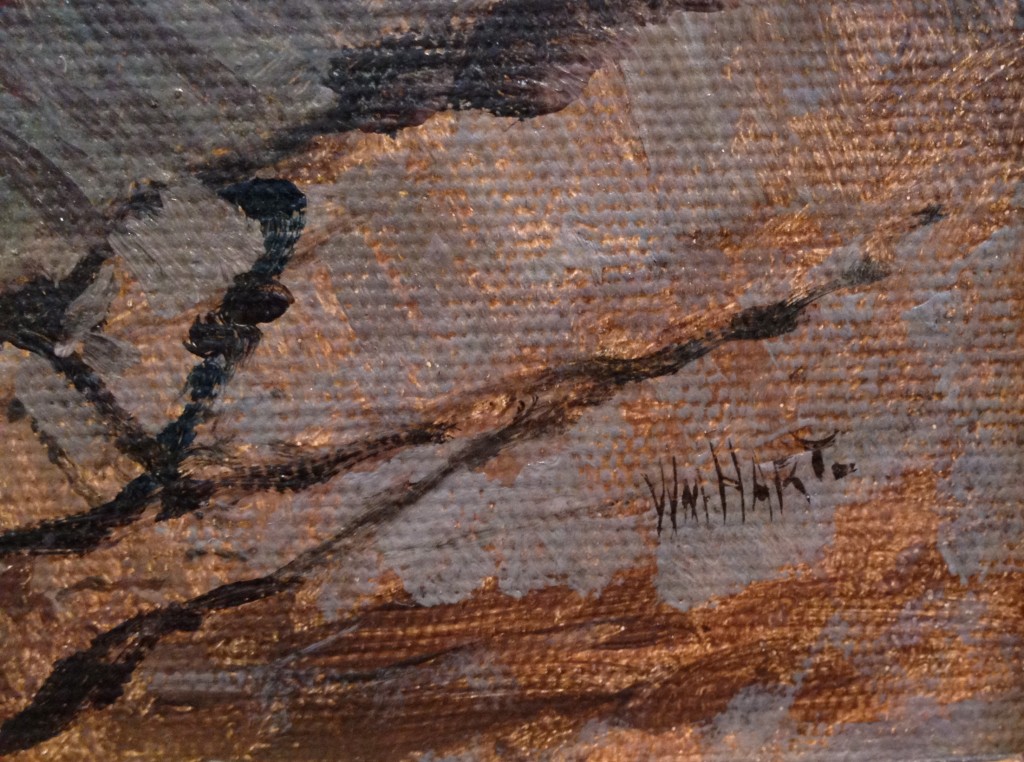

I find it significant that instead of attempting to replicate the look of marble as would other painters of the period, Leavitt purposely designs the stone’s signature mineral veins to achieve something other than mere verisimilitude. I’ve never before seen an American still life artist paint marble in this way. The veins, as ordered by Leavitt, are like meandering rivers that spread out across a wide territory. More broadly still, these lines suggest geographical markers or boundaries of territory. Some of these geographical cues refer to natural formations (we think of rivers) while others are man-made (notice the straight east-west line marking the meeting of the interlocked planes — creating “north” and “south” halves of the painting).

.

.

Both the flat backdrop slab of marble and the flat shelf that projects outward toward the viewer are of equal prominence. While we perceive these as two separate surfaces, they can also be read as sections of one partially unfolded but not yet fully flattened map, thanks in part to the implied continuation of veins from one plane to the other. Indeed, on the left side of the picture we seem to be able to observe a river, formed in the north, grow as it wends its way south. The web of arteries, while mysterious, strongly suggests this decipherment. But what, in a larger sense, is the meaning of this eerie feature of Leavitt’s composition? What does it signify in the American context of 1862?

I believe the landscape-like element of this still life represents the geography of the American Civil War.

For Leavitt to use his painter’s brush to conjure up rivers, creeks and runs in the year 1862 was inevitably to awaken the names of skirmishes and battles lately entering people’s consciousness and speech: Bull Run, Wilson’s Creek, Middle Creek, Shiloh. Even if it was the convention of just one side of the conflict (the Confederacy) to name battles after the nearest river or run, those names would have been in the thoughts and on the tongues of everyone, north and south, following news of the war, reading newspaper accounts and pouring over illustrated maps. I cannot claim the lines Leavitt etched into his unfolded stone map correspond to any actual geographical boundaries or waterways met in the path of war. They don’t have to. It served Leavitt’s purpose to create a general schematic of the water-carved fields of battle. What Leavitt intended has been successfully evoked.

.

.

.

.

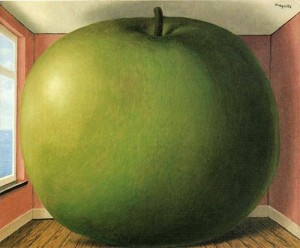

Notice also what happens to us, as viewers, when we entertain the notion, even if only for a moment, that this apple is resting on a huge expanse of territory. In our mind’s eye the apple balloons in size. Our sense of scale goes kerflooey, as happens when we look at a surrealistically large apple in a painting by Magritte.

.

.

At the very least, our sense of the meaning of the apple expands to include new possibilities.

.

2. The inflicted wound

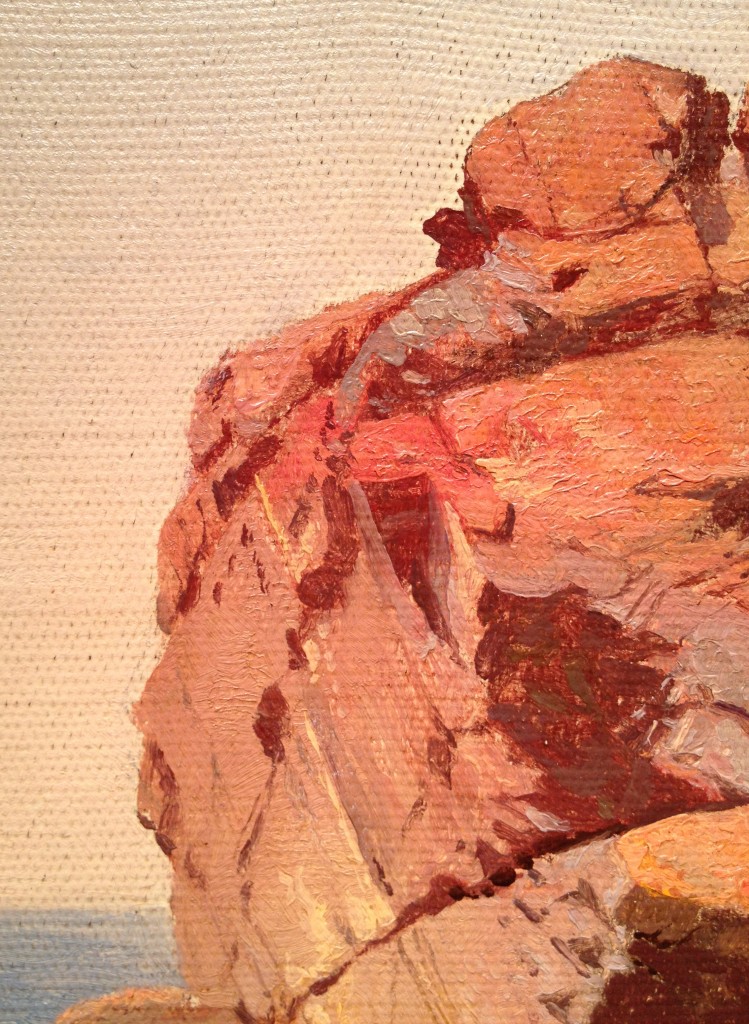

The apple has suffered a bruise. It’s a distinctive wound.

.

.

For centuries still life artists have used the trope of imperfections in the skin of a piece of fruit to signify the impermanence of beauty, illustrating the poet’s observation, “everything that grows holds in perfection but a little moment.” Yet this is almost always conveyed through depictions of naturally occurring flaws, inherent decay rising to the surface or the natural decomposition of skin post-ripeness. Apples, for example, may be shown with lesions of apple scab disease.

In contrast, the bruise Leavitt painted has a different look and meaning. It appears its cause was an irregular action, an unnatural source, something external. A plausible reading is that the wound is one inflicted by an opposing human hand, when the violent pressure of a finger and nail left a ghostly outline on the skin.

This wound occupies the southwest quadrant of the face of the apple the artist presents to the viewer. From the vantage point of Leavitt’s New England roots and his Providence, Rhode Island, home base, to the southwest is the very direction he would point, when locating the depredations of the major Civil War engagements in the year 1862. Think of Shiloh (Tennessee); Gaine’s Mill (Virginia); 2nd Battle of Bull Run (Virginia); Battle of Richmond, Kentucky; Antietam (Maryland); and Fredericksburg (Virginia).

.

3. The blood of battle

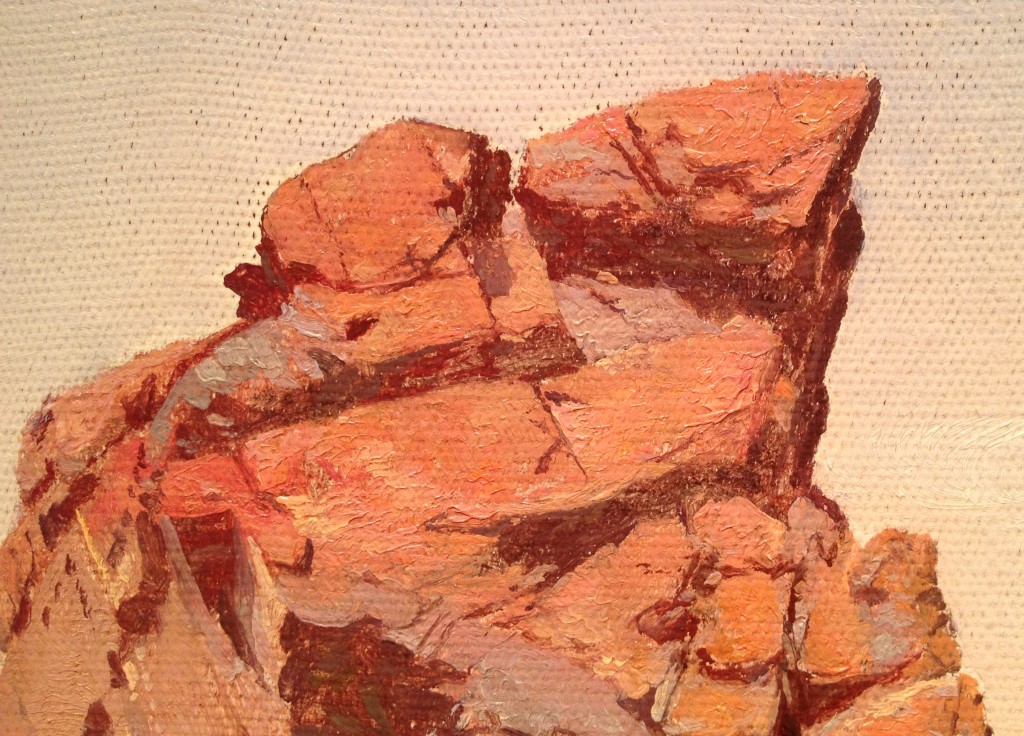

One aspect of the apple delights the eye at first glance — or at least delights the eye of a viewer who assumes this to be an innocent representation of an apple. Two drops magically cling to the apple’s skin. These two drops belong to the tradition of trompe l’oeil still life, whose practitioners applied embellishments of this sort to impart a reality to the painted object (depicting a fly alighting on the fruit is another off-used trick). Later in his career Leavitt himself would return to the practice, in one instance dotting a cabbage leaf with drops of water, and on another occasion affixing raindrops to the yellow roses and leaves in a painting from 1885:

.

.

But note that in these later examples the drops of moisture are of an entirely different character. We understand the drops on the cabbage leaf were applied externally (from refreshing rain or from being washed by man) as were those on the rose (again, from rain). In contrast, the drops on the apple appear to come from inside the apple. Just as a matter of gravity it’s hard to fathom how a drop of water could be placed on the shear side of the apple and retain its globular form. Instead we must imagine a puncture, a hole in the skin from which a vital essence slowly is escaping. The top drop appears to have just emerged. We imagine it will grow larger. The heavy bottom drop falls like a tear.

.

.

It does not matter that science can explain why the drops are red, and can assure us the drops are only behaving as lenses relaying the red color of the apple skin. No: despite such knowledge we are seized by one terrible thought. This is blood. The apple is bleeding.

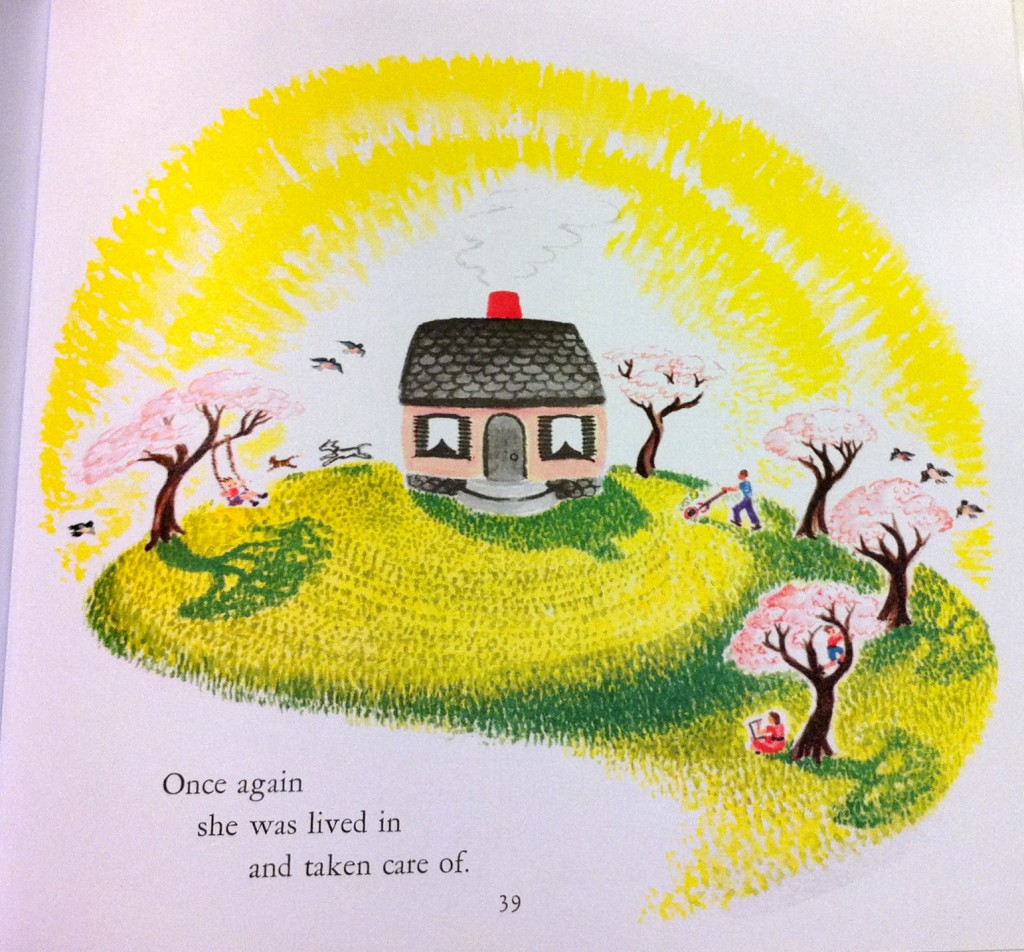

This apple was America.

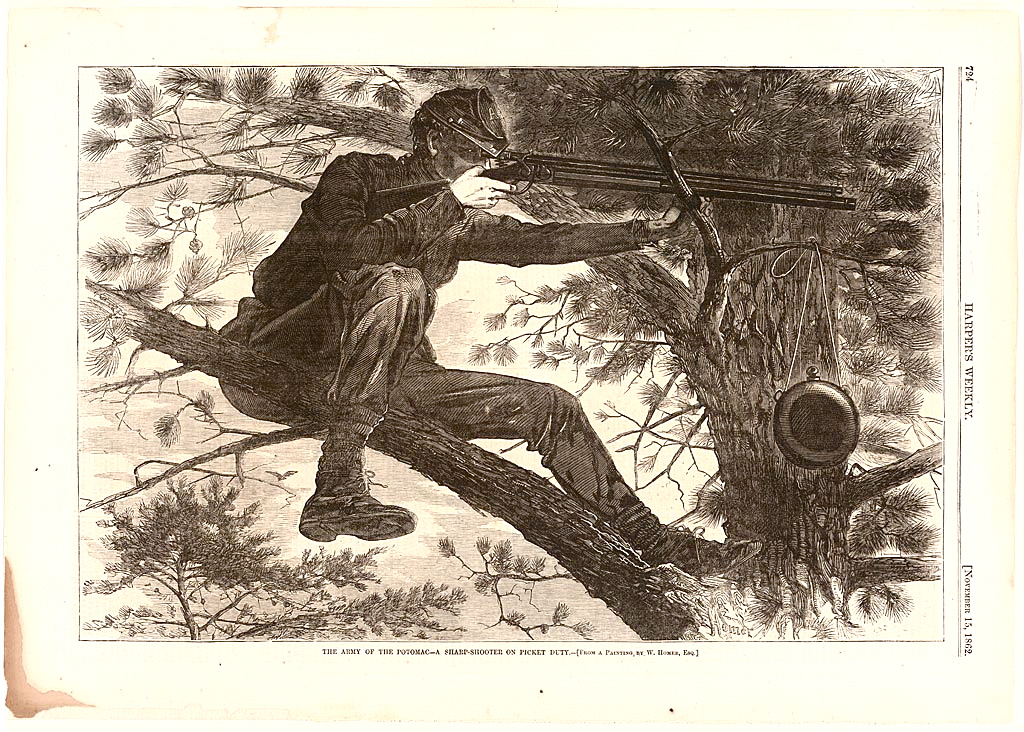

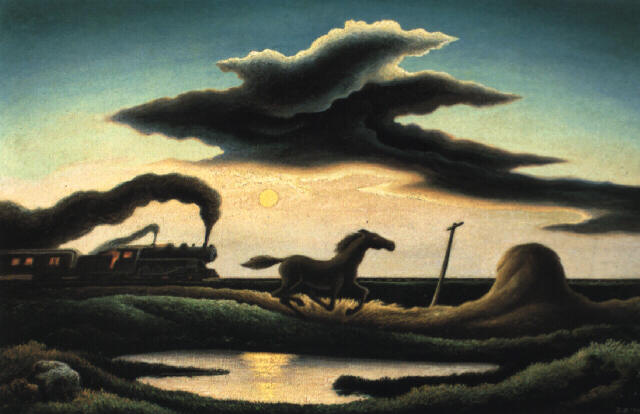

If you also admit the possibility of seeing Leavitt’s apple as a human torso, then what the young artist depicted is a mature and consequential image. In symbolic form he shows us the scene that follows the triggering scene drawn by Winslow Homer and published in Harper’s Weekly in 1862 (The Army of the Potomac–A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty). Homer called the actions of the sharp-shooter “near murder.”

.

.

___________________________________________________________

Notes and additional observations

1. As I write and post this piece, the Smithsonian American Art Museum is preparing to open an exhibition, The Civil War and American Art, that will be on view from November 16, 2012, through April 28, 2013. Later the exhibition will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, May 21 through September 3, 2013. Although the accompanying scholarly catalogue, authored by Eleanor Jones Harvey, is not yet available to me (Amazon currently lists a future release date of November 27, 2012), I’ve just read an illustrated essay, apparently an excerpt from the catalog, in American Art Review, Vol. XXIV, No. 6, 2012 (November-December), pp. 80-85. In it the author reveals her thesis that the Civil War had a profound effect on the mission, content, and uses of art in America. She focuses her analysis on landscape painting and photography as well as postwar genre painting. While those are the most obvious arenas, let me suggest the investigation into signifiers should not stop there. Still life may also respond to a war’s wounds. In the hands of an engaged artist, even a mere apple can be a nation.

2. I’ve mentioned that the web of veins in the marble platform have a mysterious aura, a mystery that activates a viewer’s desire for decipherment. In this way they remind me of the puzzling lines in the backgound of some Jasper Johns works from the 1980s and ’90s (lines whose source and meaning art scholars have scurried to uncover):

.

.

3. If, as I argue in this essay, Leavitt set his American apple upon a generalize map of the battlegrounds of Civil War America, it seems almost unnecessary to call attention to the shadow cast by the apple — the shadow of death and mourning — falling across the land. The apple cannot escape from the narrow shelf; its fate awaits. Three years later, mourning the spilling of every drop of blood, ruminating on the terrible course of events, Lincoln sadly recalled: … AND THE WAR CAME.

.